Physical fitness is related to all-cause mortality, quality of life and risk of falls in patients with type 2 diabetes. This study aimed to analyse the impact of a long-term community-based combined exercise program (aerobic+resistance+agility/balance+flexibility) developed with minimum and low-cost material resources on physical fitness in middle-aged and older patients with type 2 diabetes.

MethodsThis was a non-experimental pre-post evaluation study. Participants (N=43; 62.92±5.92 years old) were engaged in a community-based supervised exercise programme (consisting of combined aerobic, resistance, agility/balance and flexibility exercises; three sessions per week; 70min per session) of 9 months’ duration. Aerobic fitness (6-Minute Walk Test), muscle strength (30-Second Chair Stand Test), agility/balance (Timed Up and Go Test) and flexibility (Chair Sit and Reach Test) were assessed before (baseline) and after the exercise intervention.

ResultsSignificant improvements in the performance of the 6-Minute Walk Test (Δ=8.20%, p<0.001), 30-Second Chair Stand Test (Δ=28.84%, p<0.001), Timed Up and Go Test (Δ=14.31%, p<0.001), and Chair Sit and Reach Test (Δ=102.90%, p<0.001) were identified between baseline and end-exercise intervention time points.

ConclusionsA long-term community-based combined exercise programme, developed with low-cost exercise strategies, produced significant benefits in physical fitness in middle-aged and older patients with type 2 diabetes. This supervised group exercise programme significantly improved aerobic fitness, muscle strength, agility/balance and flexibility, assessed with field tests in community settings.

La aptitud física se relaciona con la mortalidad por todas las causas, la calidad de vida y el riesgo de caídas en pacientes con diabetes tipo 2. Este estudio tuvo como objetivo analizar el impacto de un programa de ejercicio combinado (aeróbico+resistido+agilidad/equilibrio+flexibilidad), a largo plazo, basado en la comunidad y desarrollado con el mínimo de recursos materiales y de bajo coste, sobre la aptitud física de pacientes de mediana edad y mayores con diabetes tipo 2.

MétodosFue un estudio de evaluación pre-post no experimental. Los/las participantes (N=43; 62,92±5,92 años) fueron implicados/as en un programa de ejercicio supervisado basado en la comunidad (compuesto por una combinación de ejercicios aeróbicos, resistidos, agilidad/equilibrio y de flexibilidad), de tres sesiones por semana (70min por sesión) durante 9 meses. La condición física aeróbica (6-Minute Walk Test), la fuerza muscular (30-Second Chair Stand Test), la agilidad/equilibrio (Timed Up and Go Test) y la flexibilidad (Chair Sit and Reach Test) se evaluaron antes (línea basal) y después de la intervención de ejercicio.

ResultadosEntre el inicio y el final del programa de ejercicio se observaron mejoras significativas en el desempeño del 6-Minute Walk Test (Δ=8,20%, p<0,001), el 30-Second Chair Stand Test (Δ=28,84%, p<0,001), el Timed Up and Go Test (Δ=14,31%, p<0,001) y el Chair Sit and Reach Test (Δ=102,90%, p<0,001).

ConclusionesUn programa de ejercicio combinado a largo plazo, basado en la comunidad y desarrollado mediante estrategias de ejercicio de bajo coste, logró beneficios significativos en la aptitud física en pacientes de mediana edad y mayores con diabetes tipo 2. Este programa de ejercicio en grupo supervisado mejoró significativamente la capacidad aeróbica, la fuerza muscular, la agilidad/equilibrio y la flexibilidad, evaluadas con pruebas de campo en un contexto comunitario.

Physical fitness has been traditionally defined as the ability to perform the daily life tasks effectively and without fatigue, and includes a variety of components, such as aerobic fitness, muscle strength, flexibility, agility and balance.1 One of the most important aspects of physical fitness is its relationship with health, and in this context it can be understood as a demonstration of skills that are associated with a lower risk of prematurely developing hypokinetic diseases.2

Type 2 diabetes is associated with low levels of physical fitness, and people with this chronic disease have lower exercise tolerance than people without diabetes.3 High levels of physical inactivity, overweight and obesity, poor glycemic control, history of cardiovascular disease, insulin resistance, endothelial dysfunction, impaired myocardial perfusion, changes in mitochondrial functions, and medication with influence on cardiovascular response to exercise, appear to be at the basis of these differences.4 Physical fitness, in particular aerobic fitness, is a strong predictor of cardiovascular events, and is inversely related to cardiovascular mortality and mortality from all causes in people with type 2 diabetes.5 Physical fitness is also associated with quality of life in this population6 and with the risk of falls,7 particularly in elderly with type 2 diabetes.

The effects of regular exercise programs developed according to exercise recommendations for people with type 2 diabetes (aerobic, resistance and flexibility exercise)8 on the main components of physical fitness appear to be well established.9–11 However, the great majority of studies have developed exercise programs with expensive equipment such as ergometers for aerobic exercise (treadmills, stationary bikes, rowing machines, steppers and ellipticals) and resistance machines for resistance exercise. The assessment of the different components of physical fitness was also performed in these expensive equipment. The access to this type of material resources represents an elevated economic cost in a population with high health expenditures, and not always is available to the majority of people with type 2 diabetes, especially in a community context, as in health care institutions, elderly institutions, city infrastructures and small clubs and associations.12

This study aimed to analyze the impact of a long-term community-based combined exercise program (aerobic+resistance+agility/balance+flexibility) developed with high applicability exercise strategies and with minimum and low-cost material resources on aerobic fitness, muscle strength, agility/balance and flexibility in middle-aged and older patients with type 2 diabetes.

MethodsStudy designThis was a non-experimental pre-post evaluation study, conducted in the city of Covilhã, Portugal, in 2013. Participants were engaged in a 9-months supervised exercise program. Aerobic fitness, muscle strength, agility/balance and flexibility were assessed before (baseline) and after the exercise program, through physical fitness field tests. Habitual physical activity was also evaluated.

ParticipantsSixty volunteers with type 2 diabetes (30 women and 30 men) were randomly selected (using a computer software) among the patients followed in a local hospital diabetology consultation who applied to participate in a long-term regular exercise program according to the following inclusion criteria: aged 55 to 75 years; diagnosis of type 2 diabetes for at least one year; glycated hemoglobin less than 10%; pharmacological regimen stabilized for at least three months; major complications of diabetes screened and controlled (diabetic retinopathy, diabetic nephropathy, diabetic foot and major cardiovascular risk factors); without limitations in gait or balance; independent living in the community; without participation in supervised exercise programs in the last 6 months; non-smokers in the last 6 months; and dietary pattern stabilized for at least 6 months.

Before study engagement all patients underwent a detailed medical evaluation to screen for relative or absolute contraindications to vigorous intensity exercise, including a maximal treadmill stress test.13,14

Study protocol has been approved by the local hospital ethics committee in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All individuals were informed of the benefits and risks of the investigation prior to signing an institutionally approved informed consent document to participate in the study.

Participants received the indication to maintain their routines of daily living (lifestyle-related physical activity, dietary pattern and pharmacological plan), and continue with diabetology consultations at the local hospital along the study duration.

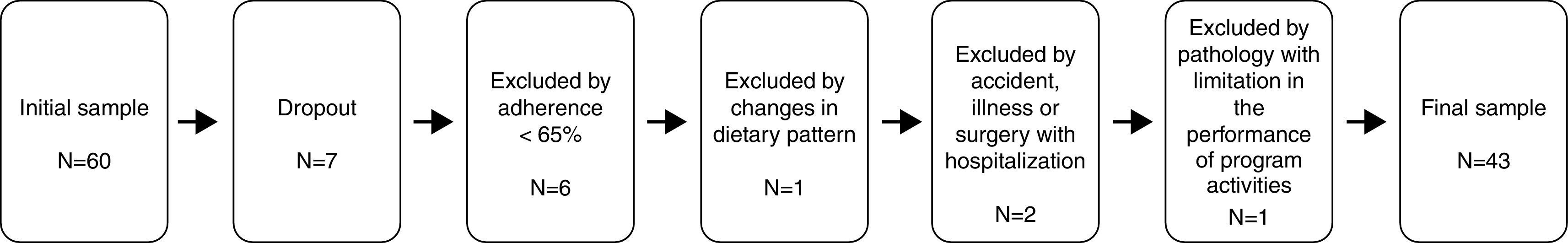

During the study the following exclusion criteria were applied (fig. 1): dropout of the exercise program (N=7); adherence to the program<65% (N=6); participation in other supervised exercise sessions (N=0); changes in dietary pattern (N=1); accident, illness or surgery with hospitalization (N=2); pathology with limitation in the performance of program activities (N=1). Final sample characteristics are presented in table 1.

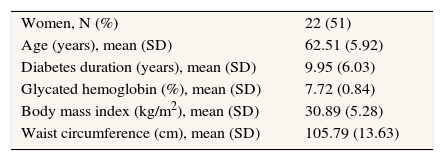

Participants’ characteristics (N=43). Covilhã, Portugal (2013).

| Women, N (%) | 22 (51) |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 62.51 (5.92) |

| Diabetes duration (years), mean (SD) | 9.95 (6.03) |

| Glycated hemoglobin (%), mean (SD) | 7.72 (0.84) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 30.89 (5.28) |

| Waist circumference (cm), mean (SD) | 105.79 (13.63) |

Aerobic fitness was assessed through the performance in the 6-Minute Walk Test (6MWT)15 –the participant is encouraged to walk as far as possible in 6minutes in a closed circuit. Muscle strength (lower limbs) was assessed through the performance in 30-Second Chair Stand Test (30SCST)16 –from the seated position, the participant is encouraged to complete as many full stands as possible within 30seconds. Agility/balance was assessed through the performance in Timed Up and Go Test (TUGT)17 –from the seated position, the participant is encouraged to rise from the chair, walk three meters, turn around, walk back to the chair, and sit down, in the shortest time possible. Flexibility (lower limbs and lumbar spine) was assessed through the performance in Chair Sit and Reach Test (CSRT)18 –seated on a chair, with the preferred leg extended and placing the right hand over the left, the participant is encouraged to slowly reach forward as far as he can by sliding his hands along the extended leg, towards the foot. All tests were conducted on the same local, by the same administrator, and with the same methodological protocol.

Habitual physical activity was evaluated using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ, short format, self-administered version).19 Final evaluations only included non-supervised physical activity in order to control lifestyle-related physical activity. IPAQ assesses the minutes per week spent on vigorous-intensity physical activities (energy expenditure of 8 METs), moderate-intensity physical activities (energy expenditure of 4 METs) and walking (energy expenditure of 3.3 METs). Total score is calculated based on the total energy expenditure of these three types of activities per week and is presented in MET-minutes/week (less than 600 MET-min/week is considerate a low level of physical activity).

Participants were engaged in Diabetes em Movimento®, a community-based exercise program developed in Portugal.20,21 The sessions of this program were held three times per week on non-consecutive days during 9 months. This exercise program was prepared according to the international exercise recommendations for patients with type 2 diabetes and also for the prevention of falls, and involved the combination of aerobic, resistance, agility/balance and flexibility exercise within each session.8,22 The exercise sessions took place in a municipal sports complex (Covilhã, Portugal), equipped with an all-weather running track, lawns, and an exercise room. Only low-cost materials were used such as chairs, water bottles filled with sand (0.5 L;±0.75kg), dumbbells (1, 2 and 3kg), fitness balls, beacons, stakes, shopping baskets, a volleyball portable kit and sports jackets. Exercise sessions were conducted in groups of 30 participants, supervised by exercise professionals and lasted about 70minutes, according to the following structure:

- 1.

Warm-up (5min) consisting of continuous brisk walking at the all-weather running track.

- 2.

Aerobic exercise (30min) at the all-weather running track and lawns, consisting of moderate-continuous brisk walking (12-13 points on Borg's scale)23 and high-intensity interval walking (relay-races, walking with external load, obstacles and stairs circuits; 14-17 points on Borg's scale).23 The ratio between moderate-continuous and high-intensity interval walking activities was 1:1.

- 3.

Resistance exercise for muscle strengthening (20min) in the exercise room. In each session six exercises were performed –three for the lower limbs and three for the upper limbs and torso– performed with bodyweight, chairs, sand bottles, dumbbells and fitness balls. Exercises were organized in circuit mode (exercises for lower limbs alternated with exercises for upper limbs and torso), with no rest between each exercise, and 1-min rest between each circuit. The number of circuits ranged progressively from one (adaptation phase) to four (last 2 months). In the bilateral exercises 20 repetitions were performed, and in the unilateral exercises 30 repetitions were performed alternately. Exercise load was selected in order to achieve local muscle fatigue during the execution of the last repetitions of each exercise. Load increase was promoted when the last repetitions of each exercise were performed without local muscle fatigue. All exercises were performed simultaneously by all participants, and the movement's execution time and the rest time were controlled by an exercise professional.

- 4.

Agility/balance exercise (10min) consisting of small-sided and conditioned team games.

- 5.

Flexibility exercise (5min) through a sequence of static and dynamic stretches performed with the support of chairs. Static positions were held for 15seconds and dynamic stretching were performed during 10 repetitions.

Five different exercise sessions were prepared, each of them with different aerobic, resistance and agility/balance exercises, successively applied over time to induce stimuli variability. Exercise sessions were planned to have moderate-to-vigorous intensity (12-17 points on a rate of perceived exertion scale with 6-20 points). Exercise intensity was systematically controlled using Borg's scale23 and adjusted if necessary during aerobic, resistance and agility/balance exercise. At the end of each session all participants were asked to register each session's overall intensity. The attendance of participants was also registered as well as the occurrence of exercise-related injuries and adverse events.

Statistical analysesTo compare the performance in physical fitness tests between the two evaluation time points, t tests for paired samples were applied. To compare the habitual physical activity (non-supervised) between the two evaluation time points, a Wilcoxon test for paired samples was applied. The level of statistical significance was set at p<0.05 and data was analyzed with PASW Statistics (version 20, SPSS Inc., Chicago). Data are shown as mean±standard deviation and as median (interquartile range) for the habitual physical activity values.

ResultsForty-three participants were included in final analysis. Adherence to the exercise program was 79.51±5.10% during the 9 months. Thirteen adverse events were recorded during the course of the exercise sessions: six symptomatic hypoglycemia (blood glucose<72mg/dL); four musculoskeletal injuries; and three non-specific indispositions. None of these events influenced the adherence results.

Exercise intensity assessed by Borg's scale23 was 12.85±1.54 points in aerobic exercise, 13.03±1.35 points in resistance exercise, 12.78±1.73 points in agility/balance exercise, and each session's overall intensity (score at the end of each session) was 13.45±1.41 points.

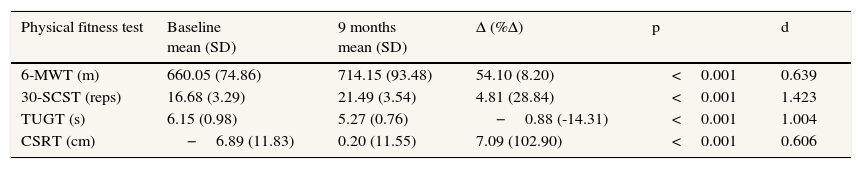

Table 2 presents the mean values in the performance of the physical fitness tests in both evaluation time points. Paired samples t tests identified significant differences (p<0.001) in the performance of 6MWT, 30SCST, TUGT, and CSRT.

Physical fitness tests performance in both evaluation time points and its variation. Covilhã, Portugal (2013).

| Physical fitness test | Baseline mean (SD) | 9 months mean (SD) | Δ (%Δ) | p | d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6-MWT (m) | 660.05 (74.86) | 714.15 (93.48) | 54.10 (8.20) | <0.001 | 0.639 |

| 30-SCST (reps) | 16.68 (3.29) | 21.49 (3.54) | 4.81 (28.84) | <0.001 | 1.423 |

| TUGT (s) | 6.15 (0.98) | 5.27 (0.76) | −0.88 (-14.31) | <0.001 | 1.004 |

| CSRT (cm) | −6.89 (11.83) | 0.20 (11.55) | 7.09 (102.90) | <0.001 | 0.606 |

Δ: variation between baseline and 9 months; p: level of significance; d: Cohen's d effect size; 6-MWT: 6-Minute Walk Test; 30-SCST: 30-Second Chair Stand Test; TUGT: Timed Up and Go Test; CSRT: Chair Sit and Reach Test; Reps: repetitions.

No significant differences were identified in habitual physical activity (non-supervised) between the two evaluation time points by the Wilcoxon test for paired samples [735.00 (925.50) vs. 773.00 (992.00) MET-min/week, p=0.461 (data not shown in tables)].

DiscussionThe main finding of the present study is that a low-cost community-based combined exercise program (aerobic+resistance+agility/balance+flexibility) induced significant benefits in aerobic fitness, muscle strength, agility/balance and flexibility in a group of middle-aged and older patients with type 2 diabetes, after nine months of intervention.

Physical fitness plays an important role in the health of this population and positive changes in physical fitness appear to predict improvements in cardiovascular risk factors independently of weight loss.24

Several studies demonstrated that a combined exercise program (aerobic+resistance+flexibility) was effective in improving aerobic fitness9,11,25, muscle strength9,10,26, and flexibility27 in individuals with type 2 diabetes, although through different exercise protocols and different intervention durations. However, these studies presented programs developed with exercise machines, such as ergometers for aerobic exercise (treadmills, stationary bikes, rowing machines, steppers and ellipticals) and/or resistance machines for resistance exercise. Although most studies have assessed aerobic fitness and muscle strength through ergometric tests and maximum repetitions tests, respectively, some of the above-mentioned works also used field tests easy to apply, as the 6MWT11,25 and 30SCST.11,26 Physical fitness assessment tests used in our study were validated against more complex laboratory tests.15,16,18 Only a minority of studies evaluated flexibility as a physical fitness outcome, despite including stretching exercises in cool-down routines.27

Among the available literature we have only found two studies28,29 that developed combined exercise programs for people with type 2 diabetes exclusively with low-cost exercise strategies: free walking combined with resistance exercises performed with bodyweight, elastic bands and free weights, and stretching exercises, even though with different exercise protocols. Aylin et al.28 observed significant improvements in muscle strength (upper and lower limbs; assessed by one repetition maximum) in a group of patients with type 2 diabetes (age 51.39±2.02 years; body mass index 28.45±0.95kg/m2; exercise adherence 96%), after an exercise program of only eight weeks, consisting of free walking (60-79% maximum heart rate) two days a week and resistance exercises performed with bodyweight and free weights in two other days. Praet et al.29 observed significant benefits in aerobic fitness (assessed through a treadmill test) in individuals with type 2 diabetes (age 61±9 years; body mass index 32.1±5.2kg/m2, exercise adherence 75±16%), after a 12-month exercise program, consisting of free walking (75% maximum heart rate) and resistance exercise performed with elastic bands and bodyweight three days a week. The last authors compared the results of the low-cost exercise intervention with a combined exercise program developed in a fitness academy with exercise machines for aerobic and resistance exercise. No significant differences were identified in aerobic fitness improvements between the two exercise programs, and 100% higher financial costs were reported in the program developed in the fitness academy.

An innovative feature of our exercise protocol was the inclusion of specific agility/balance exercises. These exercises are recommended for populations with risk of falls as the elderly,22,30 but falls are also a potential problem in individuals with diabetes since these patients have a higher risk of falling when compared with non-diabetic.7 To our knowledge only one published study integrated agility/balance exercise in a combined exercise program for individuals with type 2 diabetes. Mathieu et al.31 developed a 10-week exercise protocol (3-6 exercise sessions per week) that included aerobic, resistance, agility/balance and flexibility exercise for a group of type 2 diabetes and at-risk individuals (age 51±9 years; body mass index 30.5±6.1kg/m2, exercise adherence 82±20%). Although the inclusion of walking-based activities and resistance exercises performed with elastic bands, fitness balls and bodyweight, exercise sessions also included pool-based activities, resistance machines, group cycling, racquet activities and balance boards, which cannot be considerate low-cost exercises strategies. Significant increases in muscle strength (upper limbs; assessed by hand-grip dynamometer) and aerobic fitness (assessed by 1-Mile Walking Test) were observed, and although it was registered an improvement in balance (assessed using Functional Reach Test) this was not significant. Due to higher risk of falling, it seems important that exercise programs designed for this population incorporate agility/balance exercises, and the results of our study showed that this component of physical fitness can be significantly improved with potential benefits in falls prevention. TUGT has been recommended as a simple fall risk screening tool in community settings, especially in elderly with chronic diseases.22

Another innovative aspect of our study was the inclusion of different training methods in the development of aerobic exercise such as moderate-intensity continuous training and high-intensity interval training (HIIT). HIIT was applied in exercises like the relay-races, walking with external load and in the obstacles and stairs circuits. Vigorous-intensity exercise practice is associated with higher benefits in physical fitness in people with type 2 diabetes,32 and a HIIT program seems to induce greater benefits in aerobic fitness than a continuous training program of moderate intensity.33 Praet et al.34 developed a 10-week combined exercise program for patients with type 2 diabetes with sessions consisting of HIIT on a cycle ergometer and resistance exercise performed on resistance machines, three times a week. Significant improvements were observed in aerobic fitness and muscle strength.

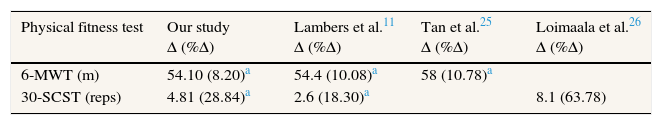

When comparing our results with the results of other studies which also used field tests to assess some components of physical fitness (despite developing the exercise programs with exercise machines) our gains in physical fitness are similar (table 3).

Comparison of physical fitness tests performance variation with other studies that used the same field tests.

| Physical fitness test | Our study Δ (%Δ) | Lambers et al.11 Δ (%Δ) | Tan et al.25 Δ (%Δ) | Loimaala et al.26 Δ (%Δ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6-MWT (m) | 54.10 (8.20)a | 54.4 (10.08)a | 58 (10.78)a | |

| 30-SCST (reps) | 4.81 (28.84)a | 2.6 (18.30)a | 8.1 (63.78) |

6-MWT: 6-Minute Walk Test; 30-SCST: 30-Second Chair Stand Test; Reps: repetitions; Δ: variation between pre- and post-test.

Like in many other studies in this area,9,10,31 our study did not include a control group to compare the results, which is a limitation. However, we evaluated the main confounding variable that could have influence on participants’ physical fitness: non-supervised habitual physical activity. This variable was assessed by the IPAQ, an international validated instrument and widely used in the population with type 2 diabetes.19,35

Another limitation is the high number of dropouts and withdrawals due to low adherence to the exercise program (21.6%). These reflect the difficulties of lifestyle intervention in this population.

All participants who integrated this study underwent a detailed medical evaluation and a maximal exercise stress test for screening for contraindications to exercise practice, in particular to vigorous-intensity exercise.13,14 In addition to the duration of diabetes, age and anthropometric profile of the participants constituted an increased risk factor. We recorded 13 exercise-related injuries and acute adverse events in the 108 exercise sessions developed during 39 weeks (nine months). They were mostly hypoglycemia associated with inadequate adjustment of insulin therapy, musculoskeletal pain associated with pre-existing osteoarticular conditions, and falls due to changes in balance inherent to the participants’ anthropometric profile and diabetes comorbidities. The concerns related to exercise sessions programming and development seem to have been important in preventing injuries, such as the progression of exercise load, the warm-up period, the pauses for hydration and the systematic monitoring of the exercise intensity. Foot observation, regular monitoring of blood glucose and blood pressure levels before and after exercise, physical contact constraint between participants in agility/balance exercises and the supervision and monitoring of the exercise sessions by professionals with training in first aid and basic life support, also contributed to the prevention of acute adverse events.14 Although most of the studies did not report data on exercise-related injuries and acute adverse events, those who did showed similar results to our study.27,29 Adherence and dropout levels observed in this study are also similar to those reported by other studies in the same area.29,31,34

Despite the above-mentioned limitations our study is strengthened by the long-term intervention (nine months), the integration of four different exercise types within each exercise session, the inclusion of high-intensity interval training method, and the exclusively use of low-cost exercise strategies and field tests.

In terms of health, this intervention can have several implications in patient's mortality, cardiovascular and musculoskeletal diseases, risk of falls and quality of life.

Future research should study the cost-effectiveness of such low-cost exercise interventions compared to traditional exercise programs using exercise machines and other expensive equipment.

In conclusion, a long-term community-based combined exercise program (aerobic+resistance+agility/balance+flexibility) developed with high applicability exercise strategies and with minimum and low-cost material resources was able to induce significant benefits in physical fitness in middle-aged and older patients with type 2 diabetes. This supervised group exercise program significantly improved aerobic fitness, muscular strength, agility/balance, and flexibility, assessed with field tests in community settings. Additionally, high-intensity interval training seems an aerobic exercise method suitable to be included in this type of interventions.

Editor in chargeM. José López.

Transparency declarationThe corresponding author on behalf of the other authors guarantee the accuracy, transparency and honesty of the data and information contained in the study, that no relevant information has been omitted and that all discrepancies between authors have been adequately resolved and described.

Physical fitness is an important issue in health and quality of life of patients with type 2 diabetes. However the evidence from the effects of exercise on physical fitness is based on exercise programs developed with expensive and complex equipment not always available to the majority of people with type 2 diabetes.

What does this study add to the literature?Low-cost exercise interventions, such as walking-based activities and resistance exercises performed with bodyweight and free weights, are effective in improving physical fitness levels and prevent falls in patients with type 2 diabetes. Supervised exercise programs combining aerobic, resistance, agility/balance and flexibility exercise should be implemented in community settings in order to improve this population's health and quality of life.

This study was funded by Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (SFRH/BD/47733/2008) and is registered in ISRCTN registry (ISRCTN09240628).

Authorship contributionsAll authors contributed to the conception and design of the work, the data collection, the analysis and interpretation of the data, the writing of the article and its critical review with important intellectual contributions, and to the approval of the final version for its publications.

Conflicts of interestsNone.