To analyse the care continuity across levels of care perceived by patients with chronic conditions in public healthcare networks in six Latin American countries (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico and Uruguay), and to explore associated factors.

MethodCross-sectional study by means of a survey conducted to a random sample of chronic patients in primary care centres of the study networks (784 per country) using the questionnaire Cuestionario de Continuidad Asistencial Entre Niveles de Atención (CCAENA)©. Patients had at least one chronic condition and had used two levels of care in the 6 months prior to the survey for the same medical condition. Descriptive analysis and multivariable logistic regression were carried out.

ResultsAlthough there are notable differences between the networks analysed, the results show that chronic patients perceive significant discontinuities in the exchange of clinical information between primary care and secondary care doctors and in access to secondary care following a referral; as well as, to a lesser degree, regarding clinical coherence across levels. Relational continuity with primary care and secondary care doctors and information transfer are positively associated with care continuity across levels; no individual factor is systematically associated with care continuity.

ConclusionsMain perceived discontinuities relate to information transfer and access to secondary care after a referral. The study indicates the importance of organisational factors to improve chronic patients’ quality of care.

Analizar la continuidad asistencial entre niveles de atención percibida por pacientes con enfermedades crónicas en redes sanitarias públicas de seis países latinoamericanos (Argentina, Brasil, Chile, Colombia, México y Uruguay) y explorar los factores asociados.

MétodoEstudio transversal mediante una encuesta realizada a una muestra aleatoria de pacientes crónicos en los centros de atención primaria de las redes de estudio (784 por país) utilizando el Cuestionario de Continuidad Asistencial Entre Niveles de Atención (CCAENA©). Los pacientes presentaban al menos una afección crónica y habían utilizado dos niveles de atención en los 6 meses anteriores a la encuesta por el mismo motivo. Se realizaron un análisis descriptivo y una regresión logística multivariante.

ResultadosAunque existen diferencias notables entre las redes analizadas, los resultados muestran que los pacientes crónicos perciben discontinuidades significativas en el intercambio de información clínica entre médicos de atención primaria y secundaria, y en el acceso a la atención secundaria tras una derivación, así como, en menor medida, en la coherencia clínica entre niveles. La continuidad de relación con los médicos de atención primaria y secundaria, y la transferencia de información, se asocian de manera positiva con la continuidad asistencial en ambos niveles; ningún factor individual se asocia sistemáticamente con la continuidad asistencial.

ConclusionesLas principales discontinuidades percibidas se relacionan con la transferencia de información y el acceso a la atención secundaria después de una derivación. El estudio indica la importancia de los factores organizativos para mejorar la calidad de la atención de los pacientes crónicos.

Latin American health systems face the challenge of improving care coordination, particularly, for patients with chronic conditions. Chronic diseases are among the major regional causes of disease burden due to the demographic and epidemiologic transition.1 Patients with chronic conditions and/or comorbidities that require care over time from different health services, are most affected by the problems commonly encountered in the region's health systems as a result of fragmentation: long waiting times;2 shortcomings in the cross-level transfer of clinical information and in establishing agreements on their clinical management;3 or a limited role of primary care as care coordinator for their care.4 Almost no study in the region analyses care continuity in a comprehensive and comparative way despite its relevance in terms of lowering health care expenditure and hospitalizations5 and its impact on improved quality of life6 and reductions in mortality.7

Reid et al.8 define continuity of care as one patient experiencing care over time as connected and coherent with their health needs and personal circumstances, and the result of care coordination. They identify three interrelated types of care continuity: 1) continuity of clinical management, or the patient's perception that they receive the different services in a coherent way that is responsive to their changing needs; 2) continuity of information, or the patient's perception that information on past events and personal circumstances is shared and used by the different providers; and 3) relational continuity, the patient's perception of an ongoing therapeutic relationship with one or more providers.

In Latin America only one study, conducted in Colombia and Brazil,3 analyses all three types of care continuity and in a comparative way. All other existing studies, mainly from Brazil, analyse care continuity as part of an assessment of care quality in primary care (PC), and focus on relational continuity with the PC doctor and accessibility only of the first care level.4,9–11 Some identify gaps in continuity between levels, mainly in the information transfer from secondary care (SC) to PC,10,11 but without addressing central issues such as continuity of clinical management, or factors related to care continuity.

On the latter subject, most studies come from high-income countries and mainly focus on factors related to the individual, with inconclusive findings concerning sex/gender or self-rated health status.12–14 More consistent findings show a negative association between high level of education and perception of continuity of clinical management and information,14–16 and a positive association between old age and perception of clinical management and relational continuity in PC.13–15 In terms of organisational factors, consistency of health professionals3,12 and being referred to SC by the PC doctor14 are associated with higher perception of continuity of information.

This article analyses care continuity in six Latin American countries (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico and Uruguay) but it forms part of a wider research project, Equity LA II, that evaluates interventions to improve coordination and continuity across care levels in their public healthcare networks.17 Public health expenditure as a percentage of gross domestic product in these countries, classified as high income (Argentina, Chile and Uruguay) and upper middle income (Brazil, Colombia and Mexico), range between 2.9% (Mexico) and 6.5% (Uruguay).18 They have different health systems models,19,20 but are segmented by population groups according to employment or socioeconomic status,1,21 with a private and a public subsystem. This latter, the focus of this study, is generally intended for the lower income population and/or those without social security and cover different proportions of population (between 36% and 76%).19 These public subsystems have similarities, including policies promoting the integration of care17 and the healthcare provision organized in networks of providers and based on primary care. The objective of this article is to analyse the care continuity across levels of care perceived by patients with chronic conditions in public healthcare networks in these countries and to explore associated factors. The results should contribute to identifying problems in care integration and to implementing changes to their improvement.

MethodStudy design and study areasA cross-sectional study was conducted based on a users’ survey using the CCAENA© questionnaire (Cuestionario de Continuidad Asistencial Entre Niveles de Atención)22 in the six countries. Two comparable public healthcare networks in urban areas were selected in each country (for further details about the networks and the selection criteria, see Vázquez et al.17).

Study population and sampleStudy population were residents of the study areas, over 18 years of age, who had at least one chronic condition and had used two care levels (PC doctor and SC doctor or emergency services) in the six months prior to the survey for the same medical condition (either chronic or acute). A sample size of 392 patients per network in each country was estimated to detect a 10% variation in patients’ perceptions of continuity of care between healthcare networks, based on 80% power (β=0.20) and 95% confidence level (α=0.05) in a bilateral contrast. Patients were selected by simple random sampling, from those waiting in PC centres. As patient registers were unavailable in some of the networks, all patients in waiting rooms, reception and clinical laboratory areas of the primary care centres were approached and those meeting the inclusion criteria were interviewed. Patients who met the criteria and refused to participate ranged from 8.9% in Colombia to 40.6% in Argentina. The final sample size was 4,881 (Table 1).

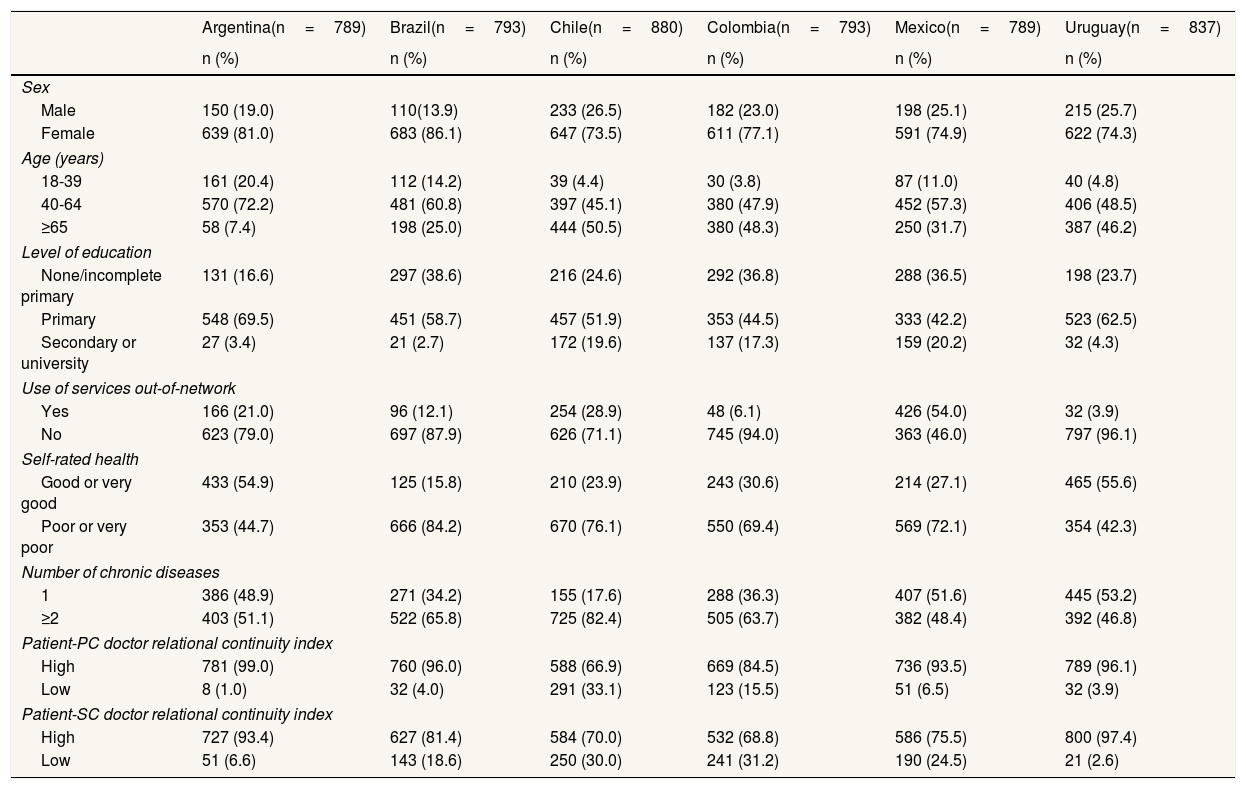

Sociodemographic characteristics, morbidity and relational continuity index of the patients’ sample (valid n and percent).

| Argentina(n=789) | Brazil(n=793) | Chile(n=880) | Colombia(n=793) | Mexico(n=789) | Uruguay(n=837) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 150 (19.0) | 110(13.9) | 233 (26.5) | 182 (23.0) | 198 (25.1) | 215 (25.7) |

| Female | 639 (81.0) | 683 (86.1) | 647 (73.5) | 611 (77.1) | 591 (74.9) | 622 (74.3) |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| 18-39 | 161 (20.4) | 112 (14.2) | 39 (4.4) | 30 (3.8) | 87 (11.0) | 40 (4.8) |

| 40-64 | 570 (72.2) | 481 (60.8) | 397 (45.1) | 380 (47.9) | 452 (57.3) | 406 (48.5) |

| ≥65 | 58 (7.4) | 198 (25.0) | 444 (50.5) | 380 (48.3) | 250 (31.7) | 387 (46.2) |

| Level of education | ||||||

| None/incomplete primary | 131 (16.6) | 297 (38.6) | 216 (24.6) | 292 (36.8) | 288 (36.5) | 198 (23.7) |

| Primary | 548 (69.5) | 451 (58.7) | 457 (51.9) | 353 (44.5) | 333 (42.2) | 523 (62.5) |

| Secondary or university | 27 (3.4) | 21 (2.7) | 172 (19.6) | 137 (17.3) | 159 (20.2) | 32 (4.3) |

| Use of services out-of-network | ||||||

| Yes | 166 (21.0) | 96 (12.1) | 254 (28.9) | 48 (6.1) | 426 (54.0) | 32 (3.9) |

| No | 623 (79.0) | 697 (87.9) | 626 (71.1) | 745 (94.0) | 363 (46.0) | 797 (96.1) |

| Self-rated health | ||||||

| Good or very good | 433 (54.9) | 125 (15.8) | 210 (23.9) | 243 (30.6) | 214 (27.1) | 465 (55.6) |

| Poor or very poor | 353 (44.7) | 666 (84.2) | 670 (76.1) | 550 (69.4) | 569 (72.1) | 354 (42.3) |

| Number of chronic diseases | ||||||

| 1 | 386 (48.9) | 271 (34.2) | 155 (17.6) | 288 (36.3) | 407 (51.6) | 445 (53.2) |

| ≥2 | 403 (51.1) | 522 (65.8) | 725 (82.4) | 505 (63.7) | 382 (48.4) | 392 (46.8) |

| Patient-PC doctor relational continuity index | ||||||

| High | 781 (99.0) | 760 (96.0) | 588 (66.9) | 669 (84.5) | 736 (93.5) | 789 (96.1) |

| Low | 8 (1.0) | 32 (4.0) | 291 (33.1) | 123 (15.5) | 51 (6.5) | 32 (3.9) |

| Patient-SC doctor relational continuity index | ||||||

| High | 727 (93.4) | 627 (81.4) | 584 (70.0) | 532 (68.8) | 586 (75.5) | 800 (97.4) |

| Low | 51 (6.6) | 143 (18.6) | 250 (30.0) | 241 (31.2) | 190 (24.5) | 21 (2.6) |

PC: primary care; SC: secondary care.

“High” corresponds to the response categories “always” or “very often”; “Low” corresponds to the response categories “rarely” or “never”.

A new version of the adapted to the Latin American context and validated version of the CCAENA© questionnaire22,23 was used. Its content was tailored to contextual and language variants of each country and translated for Brazil, by means of two pre-tests, with cognitive interviews with patients and a pilot test (20 users per country). The tool is divided into two sections: the first reconstructs the care trajectory for a specific episode within the last 6 months, and the second (this paper's object) measures patients’ perceptions of continuity.

Data collection and qualityData were collected by means of face-to-face interviews conducted by specifically trained interviewers in the PC centres from May to December 2015, except in Argentina (April 2016) and Uruguay (February 2016). To ensure the quality and consistency of data, we supervised interviewers in the field, reviewed all questionnaires, re-interviewed 20% of randomly selected participants, and used the double-entry method to control inconsistencies during data entry.

VariablesThe outcome variables are:

- •

Perception of information transfer, analysed through two questions: “My PC doctor/specialist is aware of the diagnosis, treatment and recommendations given to me by the specialist/PC doctor before I explain them to him/her”. Answers were dichotomized into high (always or very often) and low (occasionally or never).

- •

Perception of care coherence, measured by an index based on the related items (Table 2). This index was calculated by rating the response of each item from 0 to 3 points (never / rarely / very often / always). Missing values were imputed based on the mean score of the item of those observations with only one missing. The items’ scores were added and divided by their highest possible score. The index was transformed into a categorical variable representing high (more than half of the maximum score) versus low (less than half of the maximum score) perceived levels of continuity of care.

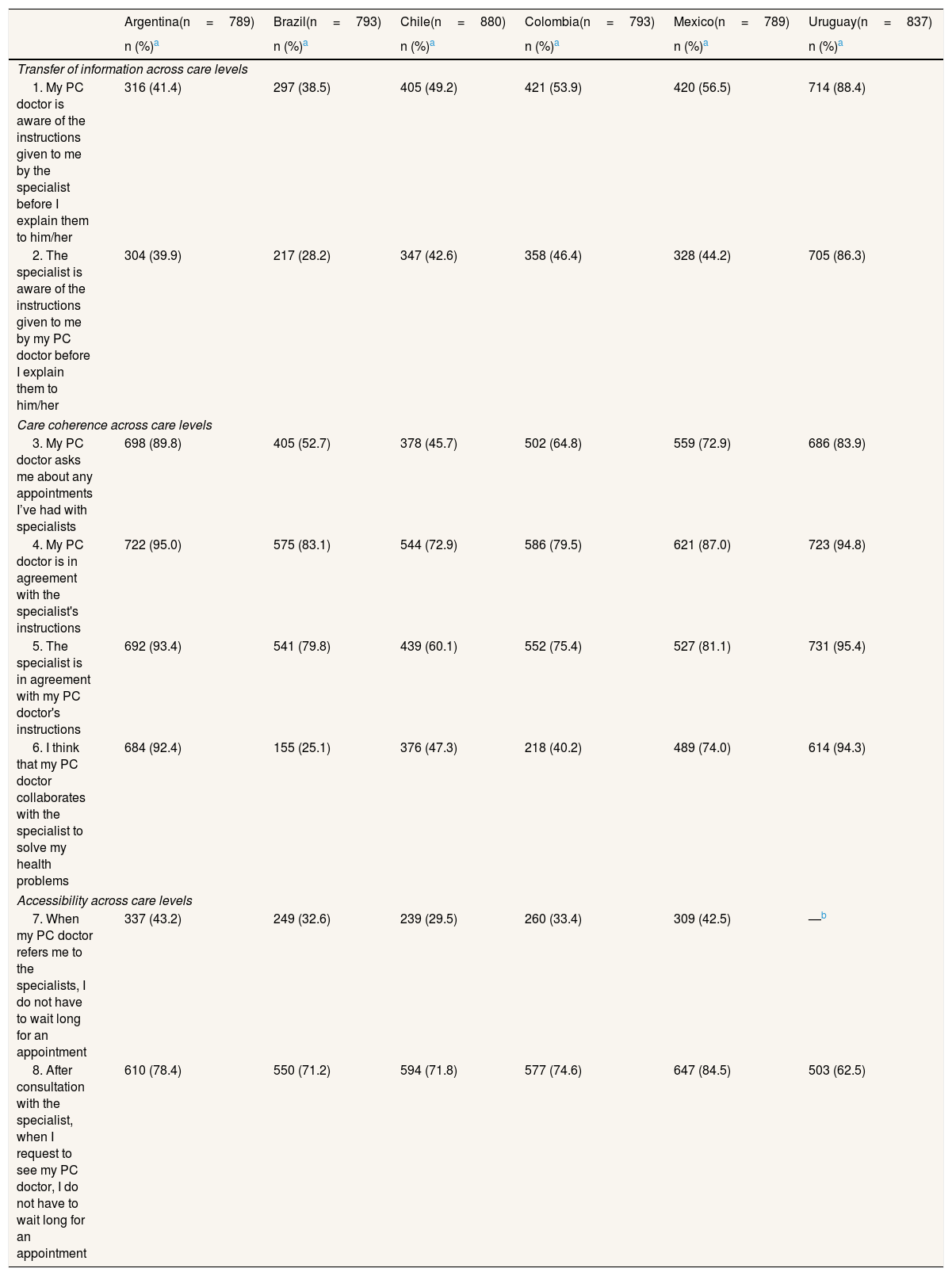

Table 2.Proportion of responses indicating high perceived cross-levels for each care continuity item, by study area.

Argentina(n=789) Brazil(n=793) Chile(n=880) Colombia(n=793) Mexico(n=789) Uruguay(n=837) n (%)a n (%)a n (%)a n (%)a n (%)a n (%)a Transfer of information across care levels 1. My PC doctor is aware of the instructions given to me by the specialist before I explain them to him/her 316 (41.4) 297 (38.5) 405 (49.2) 421 (53.9) 420 (56.5) 714 (88.4) 2. The specialist is aware of the instructions given to me by my PC doctor before I explain them to him/her 304 (39.9) 217 (28.2) 347 (42.6) 358 (46.4) 328 (44.2) 705 (86.3) Care coherence across care levels 3. My PC doctor asks me about any appointments I’ve had with specialists 698 (89.8) 405 (52.7) 378 (45.7) 502 (64.8) 559 (72.9) 686 (83.9) 4. My PC doctor is in agreement with the specialist's instructions 722 (95.0) 575 (83.1) 544 (72.9) 586 (79.5) 621 (87.0) 723 (94.8) 5. The specialist is in agreement with my PC doctor's instructions 692 (93.4) 541 (79.8) 439 (60.1) 552 (75.4) 527 (81.1) 731 (95.4) 6. I think that my PC doctor collaborates with the specialist to solve my health problems 684 (92.4) 155 (25.1) 376 (47.3) 218 (40.2) 489 (74.0) 614 (94.3) Accessibility across care levels 7. When my PC doctor refers me to the specialists, I do not have to wait long for an appointment 337 (43.2) 249 (32.6) 239 (29.5) 260 (33.4) 309 (42.5) —b 8. After consultation with the specialist, when I request to see my PC doctor, I do not have to wait long for an appointment 610 (78.4) 550 (71.2) 594 (71.8) 577 (74.6) 647 (84.5) 503 (62.5) PC: primary care.

- •

Patients’ reasons for (no) perceiving collaboration between PC and SC doctors, elicited by following up the item “I think that my PC doctor collaborates with the specialist to solve my health problems” with the open-ended question “Why?”. A content analysis of the answers was conducted.

The explanatory variables are:

- •

Sociodemographic: sex, age, level of education, and use of services out-of-network.

- •

Morbidity: number of chronic conditions according to O’Halloran's classification,24 and self-rated health, grouped into good (very good or good) and poor (poor or very poor).

- •

Relational continuity indexes: one index of relational continuity between PC doctor-patient and another of SC doctor-patient, measured by means of the respective items “Do you trust in the professional skills of the PC doctor/specialists treating you?”, “Are you given enough information by your PC doctor/specialist on your illness?” and “When you ask for an appointment with the PC doctor/specialist, are you seen by the same doctor?”. Answers were dichotomized into high (always or very often) and low (occasionally or never).

- •

Transfer of information: the items on perception of information transfer were used as explanatory variables in the analysis of the care coherence index, considering their interlinked relationship.

First a descriptive univariate analysis was performed. Logistic regression models stratified by country were then generated to assess the relationship between the three outcome variables and associated factors. Adjusted odds ratios (OR) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals were obtained. Robust covariance adjustments (employing the network variable) were used to account for correlated observations due to clustering. All the independent variables were included in the analyses. Percentages and adjusted OR were calculated for perceived high levels of continuity of care regarding information transfer and care coherence. Multicollinearity between explanatory variables was tested using the variance inflation factor (VIF), and found to be insignificant (below 1.5). Statistical analyses were performed using Stata, version 12.

Ethical considerationsEthical approval was obtained from the ethical committees in the participating countries. All interviewees participated on a voluntary basis after signing an informed consent. The right to refuse to participate or withdraw from the survey, anonymity, confidentiality and protection of data were all guaranteed.

ResultsSample characteristicsThe sample was predominantly female, with no or primary level education, and middle-aged (40 to 64 years), except in Chile and Colombia. There were notable differences between countries regarding the use of health services outside the public network (from 54% of patients in Mexico to 4% in Uruguay). More than half of the respondents rated their state of health as poor, except in Uruguay (42.3%) and Argentina (44.7%). In all countries except Uruguay (46.8%), more than half the patients suffer from two or more chronic conditions.

The participants perceived high levels of relational continuity with their PC and their SC doctors, with the highest reported in Argentina and Uruguay (over 90%) and the lowest in Chile (66.9% and 70.0%) and Colombia (84.5% and 68.8%) (Table 1).

Perception of care continuity across care levelsRegarding continuity of information, patients perceived that the PC doctor has greater knowledge of the instructions given to them previously by the SC doctor than vice versa (Table 2; see more detailed results in online supplementary Table I). Besides Uruguay, in all countries the proportion of patients perceiving high levels of information continuity is below 50%, with patients in the Brazil networks at the bottom of the scale.

With respect to continuity of clinical management, and care coherence, users perceived that PC doctors were more in agreement with the SC doctor's directions than vice versa (except in Uruguay). The highest levels for both items were found in Argentina and Uruguay (around 95%), and the lowest in Chile and Colombia (under 80%).

The percentage of patients perceiving that doctors collaborated with each other was low in Brazil (25.1%), Chile (47.3%) and Colombia (40.2%), and high in Argentina (92.4%) and Uruguay (94.3%). Information transfer and communication between PC and SC doctors, or its absence was the main reason given in all six countries for believing that doctors do (or do not) collaborate with each other (comprising 30-60% of all answers) (see online supplementary Table II).

As for accessibility between levels, most patients perceived long waiting times, mainly for consultations with the SC doctor following a referral from PC, but also for follow-up consultations with the PC doctor after the specialist (Table 2). In referrals to SC, under 60% of patients in Argentina and Mexico considered that the waiting time for their consultations was long, whilst in Chile, Brazil and Colombia, around 70% hold this opinion.

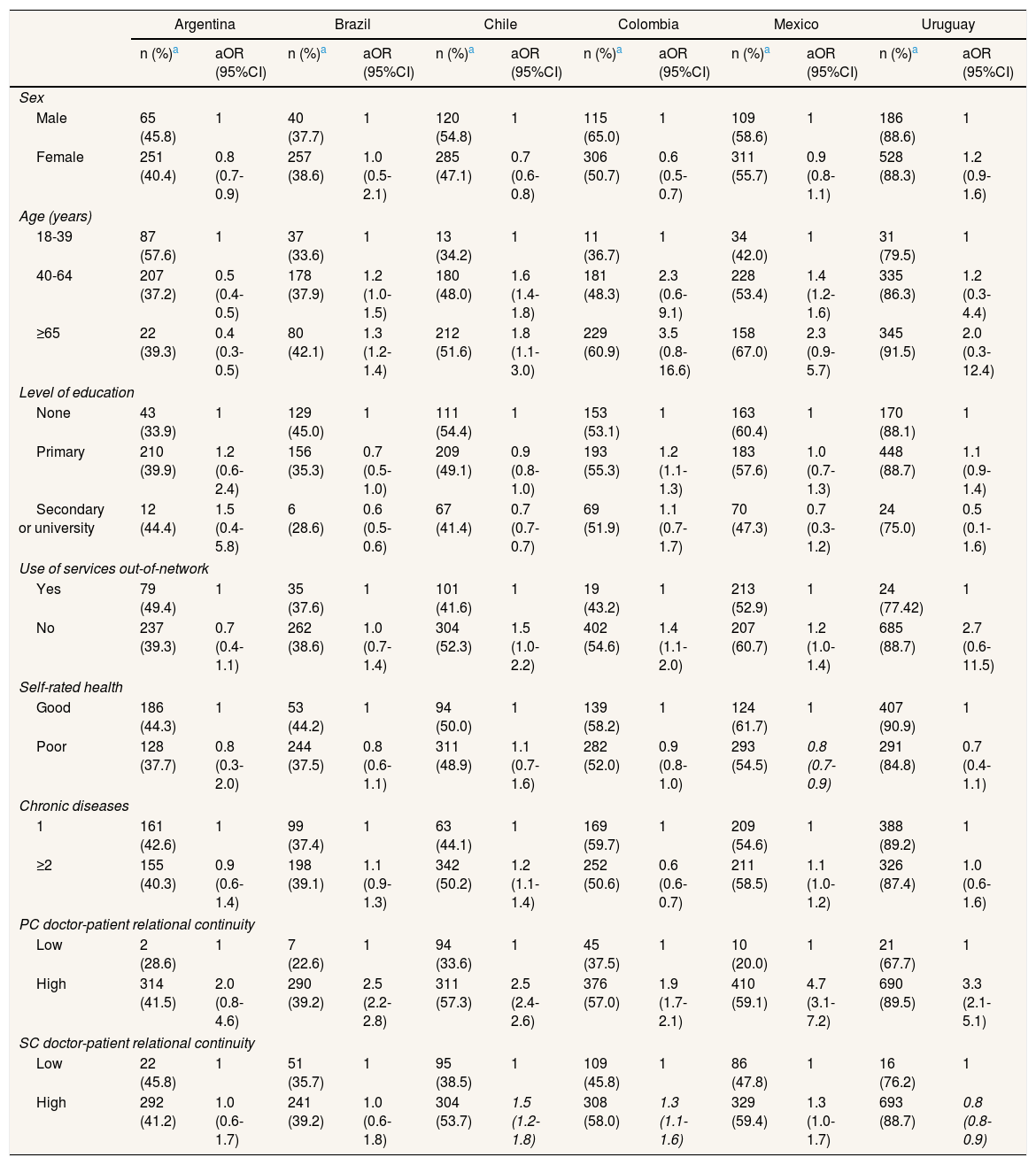

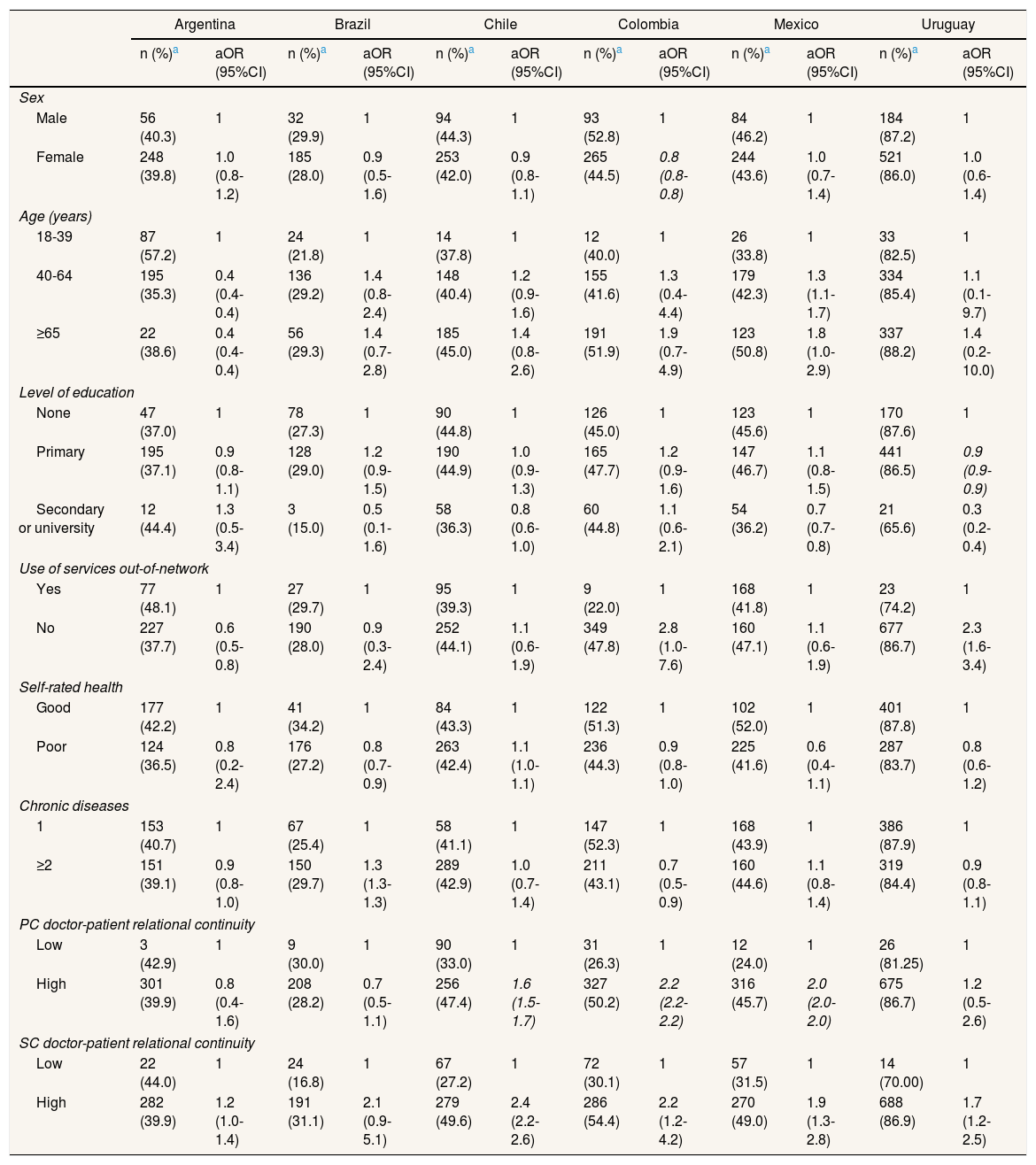

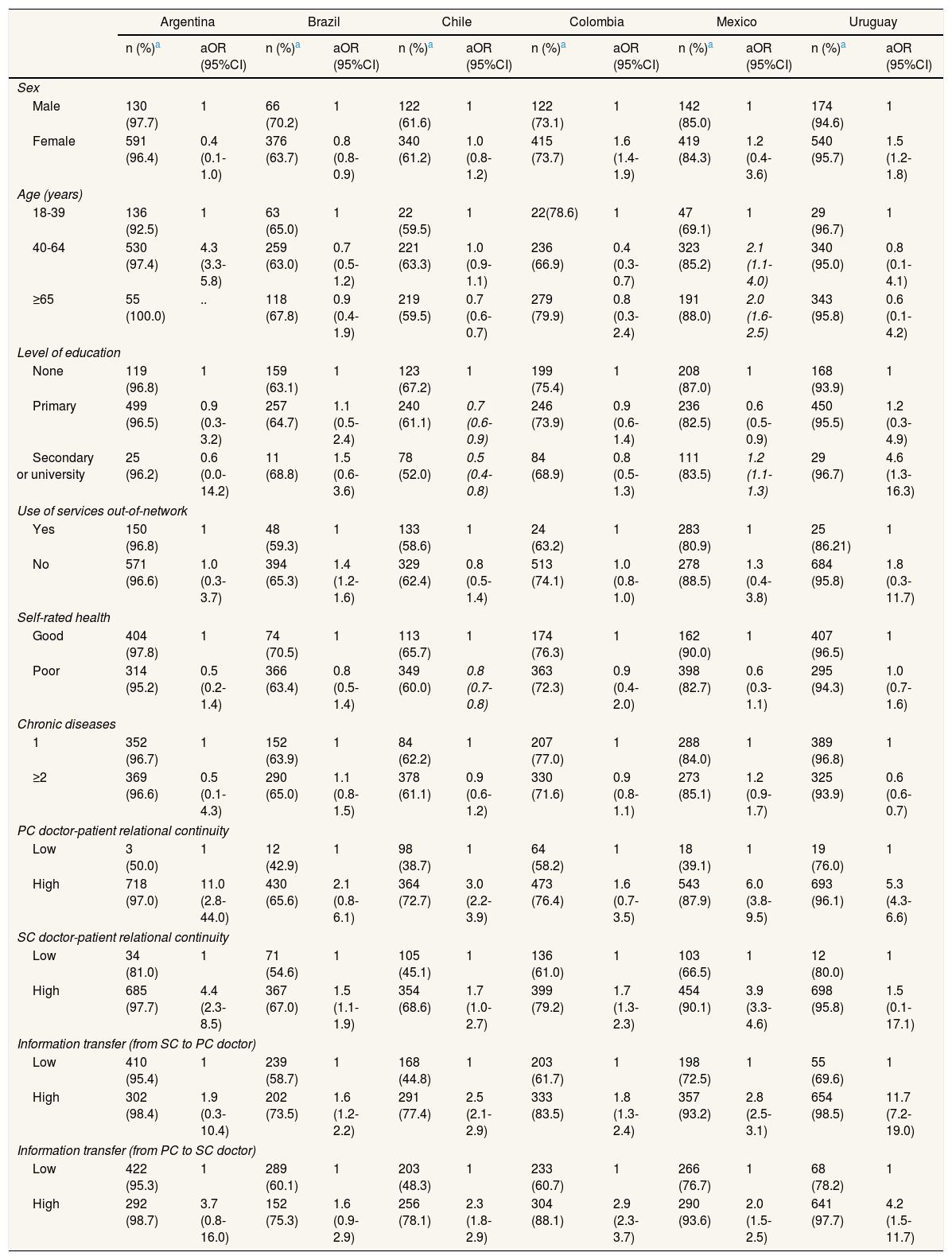

Factors associated with continuity between care levelsRelational continuity with the PC doctor and with the SC doctors were the only two factors associated in all countries with both continuity of information and continuity of clinical management between levels (Tables 3, 4 and 5). Similarly, patients perceiving high levels of information transfer between levels were also more likely to report high levels of care coherence in most of the countries (Table 5).

Factors associated with perceiving high levels of information transfer from the secondary care to primary care doctor.

| Argentina | Brazil | Chile | Colombia | Mexico | Uruguay | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%)a | aOR (95%CI) | n (%)a | aOR (95%CI) | n (%)a | aOR (95%CI) | n (%)a | aOR (95%CI) | n (%)a | aOR (95%CI) | n (%)a | aOR (95%CI) | |

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Male | 65 (45.8) | 1 | 40 (37.7) | 1 | 120 (54.8) | 1 | 115 (65.0) | 1 | 109 (58.6) | 1 | 186 (88.6) | 1 |

| Female | 251 (40.4) | 0.8 (0.7-0.9) | 257 (38.6) | 1.0 (0.5-2.1) | 285 (47.1) | 0.7 (0.6-0.8) | 306 (50.7) | 0.6 (0.5-0.7) | 311 (55.7) | 0.9 (0.8-1.1) | 528 (88.3) | 1.2 (0.9-1.6) |

| Age (years) | ||||||||||||

| 18-39 | 87 (57.6) | 1 | 37 (33.6) | 1 | 13 (34.2) | 1 | 11 (36.7) | 1 | 34 (42.0) | 1 | 31 (79.5) | 1 |

| 40-64 | 207 (37.2) | 0.5 (0.4-0.5) | 178 (37.9) | 1.2 (1.0-1.5) | 180 (48.0) | 1.6 (1.4-1.8) | 181 (48.3) | 2.3 (0.6-9.1) | 228 (53.4) | 1.4 (1.2-1.6) | 335 (86.3) | 1.2 (0.3-4.4) |

| ≥65 | 22 (39.3) | 0.4 (0.3-0.5) | 80 (42.1) | 1.3 (1.2-1.4) | 212 (51.6) | 1.8 (1.1-3.0) | 229 (60.9) | 3.5 (0.8-16.6) | 158 (67.0) | 2.3 (0.9-5.7) | 345 (91.5) | 2.0 (0.3-12.4) |

| Level of education | ||||||||||||

| None | 43 (33.9) | 1 | 129 (45.0) | 1 | 111 (54.4) | 1 | 153 (53.1) | 1 | 163 (60.4) | 1 | 170 (88.1) | 1 |

| Primary | 210 (39.9) | 1.2 (0.6-2.4) | 156 (35.3) | 0.7 (0.5-1.0) | 209 (49.1) | 0.9 (0.8-1.0) | 193 (55.3) | 1.2 (1.1-1.3) | 183 (57.6) | 1.0 (0.7-1.3) | 448 (88.7) | 1.1 (0.9-1.4) |

| Secondary or university | 12 (44.4) | 1.5 (0.4-5.8) | 6 (28.6) | 0.6 (0.5-0.6) | 67 (41.4) | 0.7 (0.7-0.7) | 69 (51.9) | 1.1 (0.7-1.7) | 70 (47.3) | 0.7 (0.3-1.2) | 24 (75.0) | 0.5 (0.1-1.6) |

| Use of services out-of-network | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 79 (49.4) | 1 | 35 (37.6) | 1 | 101 (41.6) | 1 | 19 (43.2) | 1 | 213 (52.9) | 1 | 24 (77.42) | 1 |

| No | 237 (39.3) | 0.7 (0.4-1.1) | 262 (38.6) | 1.0 (0.7-1.4) | 304 (52.3) | 1.5 (1.0-2.2) | 402 (54.6) | 1.4 (1.1-2.0) | 207 (60.7) | 1.2 (1.0-1.4) | 685 (88.7) | 2.7 (0.6-11.5) |

| Self-rated health | ||||||||||||

| Good | 186 (44.3) | 1 | 53 (44.2) | 1 | 94 (50.0) | 1 | 139 (58.2) | 1 | 124 (61.7) | 1 | 407 (90.9) | 1 |

| Poor | 128 (37.7) | 0.8 (0.3-2.0) | 244 (37.5) | 0.8 (0.6-1.1) | 311 (48.9) | 1.1 (0.7-1.6) | 282 (52.0) | 0.9 (0.8-1.0) | 293 (54.5) | 0.8 (0.7-0.9) | 291 (84.8) | 0.7 (0.4-1.1) |

| Chronic diseases | ||||||||||||

| 1 | 161 (42.6) | 1 | 99 (37.4) | 1 | 63 (44.1) | 1 | 169 (59.7) | 1 | 209 (54.6) | 1 | 388 (89.2) | 1 |

| ≥2 | 155 (40.3) | 0.9 (0.6-1.4) | 198 (39.1) | 1.1 (0.9-1.3) | 342 (50.2) | 1.2 (1.1-1.4) | 252 (50.6) | 0.6 (0.6-0.7) | 211 (58.5) | 1.1 (1.0-1.2) | 326 (87.4) | 1.0 (0.6-1.6) |

| PC doctor-patient relational continuity | ||||||||||||

| Low | 2 (28.6) | 1 | 7 (22.6) | 1 | 94 (33.6) | 1 | 45 (37.5) | 1 | 10 (20.0) | 1 | 21 (67.7) | 1 |

| High | 314 (41.5) | 2.0 (0.8-4.6) | 290 (39.2) | 2.5 (2.2-2.8) | 311 (57.3) | 2.5 (2.4-2.6) | 376 (57.0) | 1.9 (1.7-2.1) | 410 (59.1) | 4.7 (3.1-7.2) | 690 (89.5) | 3.3 (2.1-5.1) |

| SC doctor-patient relational continuity | ||||||||||||

| Low | 22 (45.8) | 1 | 51 (35.7) | 1 | 95 (38.5) | 1 | 109 (45.8) | 1 | 86 (47.8) | 1 | 16 (76.2) | 1 |

| High | 292 (41.2) | 1.0 (0.6-1.7) | 241 (39.2) | 1.0 (0.6-1.8) | 304 (53.7) | 1.5 (1.2-1.8) | 308 (58.0) | 1.3 (1.1-1.6) | 329 (59.4) | 1.3 (1.0-1.7) | 693 (88.7) | 0.8 (0.8-0.9) |

aOR: adjusted odds ratio; 95%CI: 95% confidence interval; PC: primary care; SC: secondary care.

Factors associated with perceiving higher levels of information transfer from the primary care to secondary care doctor.

| Argentina | Brazil | Chile | Colombia | Mexico | Uruguay | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%)a | aOR (95%CI) | n (%)a | aOR (95%CI) | n (%)a | aOR (95%CI) | n (%)a | aOR (95%CI) | n (%)a | aOR (95%CI) | n (%)a | aOR (95%CI) | |

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Male | 56 (40.3) | 1 | 32 (29.9) | 1 | 94 (44.3) | 1 | 93 (52.8) | 1 | 84 (46.2) | 1 | 184 (87.2) | 1 |

| Female | 248 (39.8) | 1.0 (0.8-1.2) | 185 (28.0) | 0.9 (0.5-1.6) | 253 (42.0) | 0.9 (0.8-1.1) | 265 (44.5) | 0.8 (0.8-0.8) | 244 (43.6) | 1.0 (0.7-1.4) | 521 (86.0) | 1.0 (0.6-1.4) |

| Age (years) | ||||||||||||

| 18-39 | 87 (57.2) | 1 | 24 (21.8) | 1 | 14 (37.8) | 1 | 12 (40.0) | 1 | 26 (33.8) | 1 | 33 (82.5) | 1 |

| 40-64 | 195 (35.3) | 0.4 (0.4-0.4) | 136 (29.2) | 1.4 (0.8-2.4) | 148 (40.4) | 1.2 (0.9-1.6) | 155 (41.6) | 1.3 (0.4-4.4) | 179 (42.3) | 1.3 (1.1-1.7) | 334 (85.4) | 1.1 (0.1-9.7) |

| ≥65 | 22 (38.6) | 0.4 (0.4-0.4) | 56 (29.3) | 1.4 (0.7-2.8) | 185 (45.0) | 1.4 (0.8-2.6) | 191 (51.9) | 1.9 (0.7-4.9) | 123 (50.8) | 1.8 (1.0-2.9) | 337 (88.2) | 1.4 (0.2-10.0) |

| Level of education | ||||||||||||

| None | 47 (37.0) | 1 | 78 (27.3) | 1 | 90 (44.8) | 1 | 126 (45.0) | 1 | 123 (45.6) | 1 | 170 (87.6) | 1 |

| Primary | 195 (37.1) | 0.9 (0.8-1.1) | 128 (29.0) | 1.2 (0.9-1.5) | 190 (44.9) | 1.0 (0.9-1.3) | 165 (47.7) | 1.2 (0.9-1.6) | 147 (46.7) | 1.1 (0.8-1.5) | 441 (86.5) | 0.9 (0.9-0.9) |

| Secondary or university | 12 (44.4) | 1.3 (0.5-3.4) | 3 (15.0) | 0.5 (0.1-1.6) | 58 (36.3) | 0.8 (0.6-1.0) | 60 (44.8) | 1.1 (0.6-2.1) | 54 (36.2) | 0.7 (0.7-0.8) | 21 (65.6) | 0.3 (0.2-0.4) |

| Use of services out-of-network | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 77 (48.1) | 1 | 27 (29.7) | 1 | 95 (39.3) | 1 | 9 (22.0) | 1 | 168 (41.8) | 1 | 23 (74.2) | 1 |

| No | 227 (37.7) | 0.6 (0.5-0.8) | 190 (28.0) | 0.9 (0.3-2.4) | 252 (44.1) | 1.1 (0.6-1.9) | 349 (47.8) | 2.8 (1.0-7.6) | 160 (47.1) | 1.1 (0.6-1.9) | 677 (86.7) | 2.3 (1.6-3.4) |

| Self-rated health | ||||||||||||

| Good | 177 (42.2) | 1 | 41 (34.2) | 1 | 84 (43.3) | 1 | 122 (51.3) | 1 | 102 (52.0) | 1 | 401 (87.8) | 1 |

| Poor | 124 (36.5) | 0.8 (0.2-2.4) | 176 (27.2) | 0.8 (0.7-0.9) | 263 (42.4) | 1.1 (1.0-1.1) | 236 (44.3) | 0.9 (0.8-1.0) | 225 (41.6) | 0.6 (0.4-1.1) | 287 (83.7) | 0.8 (0.6-1.2) |

| Chronic diseases | ||||||||||||

| 1 | 153 (40.7) | 1 | 67 (25.4) | 1 | 58 (41.1) | 1 | 147 (52.3) | 1 | 168 (43.9) | 1 | 386 (87.9) | 1 |

| ≥2 | 151 (39.1) | 0.9 (0.8-1.0) | 150 (29.7) | 1.3 (1.3-1.3) | 289 (42.9) | 1.0 (0.7-1.4) | 211 (43.1) | 0.7 (0.5-0.9) | 160 (44.6) | 1.1 (0.8-1.4) | 319 (84.4) | 0.9 (0.8-1.1) |

| PC doctor-patient relational continuity | ||||||||||||

| Low | 3 (42.9) | 1 | 9 (30.0) | 1 | 90 (33.0) | 1 | 31 (26.3) | 1 | 12 (24.0) | 1 | 26 (81.25) | 1 |

| High | 301 (39.9) | 0.8 (0.4-1.6) | 208 (28.2) | 0.7 (0.5-1.1) | 256 (47.4) | 1.6 (1.5-1.7) | 327 (50.2) | 2.2 (2.2-2.2) | 316 (45.7) | 2.0 (2.0-2.0) | 675 (86.7) | 1.2 (0.5-2.6) |

| SC doctor-patient relational continuity | ||||||||||||

| Low | 22 (44.0) | 1 | 24 (16.8) | 1 | 67 (27.2) | 1 | 72 (30.1) | 1 | 57 (31.5) | 1 | 14 (70.00) | 1 |

| High | 282 (39.9) | 1.2 (1.0-1.4) | 191 (31.1) | 2.1 (0.9-5.1) | 279 (49.6) | 2.4 (2.2-2.6) | 286 (54.4) | 2.2 (1.2-4.2) | 270 (49.0) | 1.9 (1.3-2.8) | 688 (86.9) | 1.7 (1.2-2.5) |

aOR: adjusted odds ratio; 95%CI: 95% confidence interval; PC: primary care; SC: secondary care.

Factors associated with perceiving higher levels of care coherence.

| Argentina | Brazil | Chile | Colombia | Mexico | Uruguay | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%)a | aOR (95%CI) | n (%)a | aOR (95%CI) | n (%)a | aOR (95%CI) | n (%)a | aOR (95%CI) | n (%)a | aOR (95%CI) | n (%)a | aOR (95%CI) | |

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Male | 130 (97.7) | 1 | 66 (70.2) | 1 | 122 (61.6) | 1 | 122 (73.1) | 1 | 142 (85.0) | 1 | 174 (94.6) | 1 |

| Female | 591 (96.4) | 0.4 (0.1-1.0) | 376 (63.7) | 0.8 (0.8-0.9) | 340 (61.2) | 1.0 (0.8-1.2) | 415 (73.7) | 1.6 (1.4-1.9) | 419 (84.3) | 1.2 (0.4-3.6) | 540 (95.7) | 1.5 (1.2-1.8) |

| Age (years) | ||||||||||||

| 18-39 | 136 (92.5) | 1 | 63 (65.0) | 1 | 22 (59.5) | 1 | 22(78.6) | 1 | 47 (69.1) | 1 | 29 (96.7) | 1 |

| 40-64 | 530 (97.4) | 4.3 (3.3-5.8) | 259 (63.0) | 0.7 (0.5-1.2) | 221 (63.3) | 1.0 (0.9-1.1) | 236 (66.9) | 0.4 (0.3-0.7) | 323 (85.2) | 2.1 (1.1-4.0) | 340 (95.0) | 0.8 (0.1-4.1) |

| ≥65 | 55 (100.0) | .. | 118 (67.8) | 0.9 (0.4-1.9) | 219 (59.5) | 0.7 (0.6-0.7) | 279 (79.9) | 0.8 (0.3-2.4) | 191 (88.0) | 2.0 (1.6-2.5) | 343 (95.8) | 0.6 (0.1-4.2) |

| Level of education | ||||||||||||

| None | 119 (96.8) | 1 | 159 (63.1) | 1 | 123 (67.2) | 1 | 199 (75.4) | 1 | 208 (87.0) | 1 | 168 (93.9) | 1 |

| Primary | 499 (96.5) | 0.9 (0.3-3.2) | 257 (64.7) | 1.1 (0.5-2.4) | 240 (61.1) | 0.7 (0.6-0.9) | 246 (73.9) | 0.9 (0.6-1.4) | 236 (82.5) | 0.6 (0.5-0.9) | 450 (95.5) | 1.2 (0.3-4.9) |

| Secondary or university | 25 (96.2) | 0.6 (0.0-14.2) | 11 (68.8) | 1.5 (0.6-3.6) | 78 (52.0) | 0.5 (0.4-0.8) | 84 (68.9) | 0.8 (0.5-1.3) | 111 (83.5) | 1.2 (1.1-1.3) | 29 (96.7) | 4.6 (1.3-16.3) |

| Use of services out-of-network | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 150 (96.8) | 1 | 48 (59.3) | 1 | 133 (58.6) | 1 | 24 (63.2) | 1 | 283 (80.9) | 1 | 25 (86.21) | 1 |

| No | 571 (96.6) | 1.0 (0.3-3.7) | 394 (65.3) | 1.4 (1.2-1.6) | 329 (62.4) | 0.8 (0.5-1.4) | 513 (74.1) | 1.0 (0.8-1.0) | 278 (88.5) | 1.3 (0.4-3.8) | 684 (95.8) | 1.8 (0.3-11.7) |

| Self-rated health | ||||||||||||

| Good | 404 (97.8) | 1 | 74 (70.5) | 1 | 113 (65.7) | 1 | 174 (76.3) | 1 | 162 (90.0) | 1 | 407 (96.5) | 1 |

| Poor | 314 (95.2) | 0.5 (0.2-1.4) | 366 (63.4) | 0.8 (0.5-1.4) | 349 (60.0) | 0.8 (0.7-0.8) | 363 (72.3) | 0.9 (0.4-2.0) | 398 (82.7) | 0.6 (0.3-1.1) | 295 (94.3) | 1.0 (0.7-1.6) |

| Chronic diseases | ||||||||||||

| 1 | 352 (96.7) | 1 | 152 (63.9) | 1 | 84 (62.2) | 1 | 207 (77.0) | 1 | 288 (84.0) | 1 | 389 (96.8) | 1 |

| ≥2 | 369 (96.6) | 0.5 (0.1-4.3) | 290 (65.0) | 1.1 (0.8-1.5) | 378 (61.1) | 0.9 (0.6-1.2) | 330 (71.6) | 0.9 (0.8-1.1) | 273 (85.1) | 1.2 (0.9-1.7) | 325 (93.9) | 0.6 (0.6-0.7) |

| PC doctor-patient relational continuity | ||||||||||||

| Low | 3 (50.0) | 1 | 12 (42.9) | 1 | 98 (38.7) | 1 | 64 (58.2) | 1 | 18 (39.1) | 1 | 19 (76.0) | 1 |

| High | 718 (97.0) | 11.0 (2.8-44.0) | 430 (65.6) | 2.1 (0.8-6.1) | 364 (72.7) | 3.0 (2.2-3.9) | 473 (76.4) | 1.6 (0.7-3.5) | 543 (87.9) | 6.0 (3.8-9.5) | 693 (96.1) | 5.3 (4.3-6.6) |

| SC doctor-patient relational continuity | ||||||||||||

| Low | 34 (81.0) | 1 | 71 (54.6) | 1 | 105 (45.1) | 1 | 136 (61.0) | 1 | 103 (66.5) | 1 | 12 (80.0) | 1 |

| High | 685 (97.7) | 4.4 (2.3-8.5) | 367 (67.0) | 1.5 (1.1-1.9) | 354 (68.6) | 1.7 (1.0-2.7) | 399 (79.2) | 1.7 (1.3-2.3) | 454 (90.1) | 3.9 (3.3-4.6) | 698 (95.8) | 1.5 (0.1-17.1) |

| Information transfer (from SC to PC doctor) | ||||||||||||

| Low | 410 (95.4) | 1 | 239 (58.7) | 1 | 168 (44.8) | 1 | 203 (61.7) | 1 | 198 (72.5) | 1 | 55 (69.6) | 1 |

| High | 302 (98.4) | 1.9 (0.3-10.4) | 202 (73.5) | 1.6 (1.2-2.2) | 291 (77.4) | 2.5 (2.1-2.9) | 333 (83.5) | 1.8 (1.3-2.4) | 357 (93.2) | 2.8 (2.5-3.1) | 654 (98.5) | 11.7 (7.2-19.0) |

| Information transfer (from PC to SC doctor) | ||||||||||||

| Low | 422 (95.3) | 1 | 289 (60.1) | 1 | 203 (48.3) | 1 | 233 (60.7) | 1 | 266 (76.7) | 1 | 68 (78.2) | 1 |

| High | 292 (98.7) | 3.7 (0.8-16.0) | 152 (75.3) | 1.6 (0.9-2.9) | 256 (78.1) | 2.3 (1.8-2.9) | 304 (88.1) | 2.9 (2.3-3.7) | 290 (93.6) | 2.0 (1.5-2.5) | 641 (97.7) | 4.2 (1.5-11.7) |

aOR: adjusted odds ratio; 95%CI: 95% confidence interval; PC: primary care; SC: secondary care.

Regarding individual characteristics, the clearest association is between continuity of information and sex: being female tends to be negatively associated with the perception of information transfer from the SC doctor to the PC doctor (Tables 3 and 4).

DiscussionThis study provides evidence on a little explored phenomenon in Latin America: continuity across care levels for patients with chronic diseases and associated factors in public healthcare networks in six countries. The results complement the analysis of care coordination performed in the same networks via a survey of PC and SC doctors.19,20

Differences in continuity across care levels in the networks of the six countriesPatients in the networks analysed have a worse perception of transfer of information and accessibility to SC than of care coherence, coinciding with the experience of doctors in these networks.25 Yet, we observe differences between countries: highest levels of continuity of information across levels are perceived in Uruguay, and also higher levels of care coherence in both Uruguay and Argentina, but with less substantial differences. These differences may be attributable to certain characteristics of the networks studied in Uruguay (smaller size, located in smaller urban areas and with co-location of PC and SC doctors in polyclinics) which foster that doctors know each other personally as well as mutual trust and informal communication between them,25 and facilitates the information exchange and agreement on treatments. Regarding Argentina, it may be related to the assignment of specialist as referral teams to PC centres for certain specialities26 which could favour collaboration and agreement among PC and SC doctors, as well as relational continuity with SC, since patients assigned to a particular PC doctor would generally be seen by the same specialists.

The doctors’ perspective on equivalent aspects such as the transfer of information or agreement on treatments was generally worse.25 Doctors are probably more critical because they encounter coordination problems with the other care level on a daily basis, whereas patients probably only perceive coordination problems when these have a negative impact on the quality of their care.27 Nevertheless, patients also perceived significant discontinuities between care levels. They perceive them in the transfer of clinical information between levels, which is related to doctors’ deficient use of referral and reply letters.20 Also, significant discontinuities were perceived by patients in access to SC following referral by a PC doctor. The long waiting times reported indicate delays or interruptions in the diagnosis and treatment of chronic patients that could result in late diagnosis, upsets and complications, as previous qualitative studies pointed out.25

Relational continuity with PC and SC doctors and information transfer are associated with care continuity between levelsOne of the most relevant results of this study is that it is the organisational factors (relational continuity with the PC doctor and the SC doctor, and information transfer between levels), and not the individual characteristics of chronic patients, that are consistently associated in the same way in nearly all countries: relational continuity with perceiving high levels of both types of care continuity between levels, and information transfer with care coherence. This finding is consistent with previous studies.3,14,28 However, our results also highlight the importance, not only of being seen by the same doctor, but also of the quality of the bond established between patient and doctor in both PC and SC, for continuity of care between levels to exist for chronic patients. Relational continuity appears to favour a doctors’ knowledge of the patient's medical history across the care continuum and, at the same time, ease the process of agreeing on a treatment plan with doctors of the other level. Indeed, the frequent staff turnover in Chile and Colombia (more than 60% of doctors on temporary contracts in the first case and nearly 80% in the second, compared to 20% in the other countries),19 may serve to explain the more negative perception of continuity between care levels in these countries.

Another relevant finding is the association between the perception of information transfer and care coherence, described in qualitative studies,29 that point out that the transfer of information between levels facilitates agreement between PC and SC doctors on patient diagnosis and treatment. This association may explain why patients in Brazil, Chile and Colombia, with a worse perception of information continuity, also have a worse perception of care coherence.

LimitationsGiven the lack of records on chronic patients’ use of services in some networks, patients were selected in the PC health centres, and they were interviewed on the premises. This may have influenced their responses for instance by inhibiting to express their real opinions or owing to distraction. Also, survey fatigue cannot be excluded. After the pilot test, the original CCAENA recall period was extended from 3 months to 6 given the patients’ difficulties in the study countries to access another care level, which may have led to recall bias. Additionally, as this is a cross-sectional study it does not allow us to determine causality but rather association between factors. Furthermore, the dichotomization of indexes to facilitate the interpretation of data could lead to some loss of information.

ConclusionPatients with chronic conditions in the countries analysed (albeit with differences between the networks) perceive significant discontinuities in the exchange of clinical information between PC and SC doctors and in access to SC, and to a lesser degree, a lack of coherence in their care. The analysis of associated factors indicates that improving continuity of care between levels for these patients entails strengthening their relation continuity with both the PC and SC doctor and fostering communication between doctors.

Patients with chronic conditions are particularly vulnerable to experiencing discontinuities in their care. Latin America health systems with their severe fragmentation face the challenge of an increase in chronic diseases.

What does this study add to the literature?This study provides comprehensive evidence on continuity across care levels for patients with chronic diseases and associated factors in public healthcare networks of six Latin American countries. Results stress the need to implement policies to improve organizational factors, such as accessibility and coordination of clinical information between levels and to strengthen relational continuity.

Carlos Álvarez-Dardet.

Transparency declarationThe corresponding author on behalf of the other authors guarantee the accuracy, transparency and honesty of the data and information contained in the study, that no relevant information has been omitted and that all discrepancies between authors have been adequately resolved and described.

Authorship contributionsAll of the authors made essential contributions to the study, namely L. Ollé-Espluga prepared the databases, performed statistical analysis, and, together with M.L. Vázquez and I. Vargas, interpreted the results and wrote the first version of the manuscript. M.L. Vázquez and I. Vargas are responsible for the project, designed the study, supervised all the stages of its development, contributed to the interpretation of the results and to the writing of the manuscript. A. Mogollón-Pérez, P. Eguiguren, R.P. Freitas Soares-de-Jesus, A.I. Cisneros, M.C. Muruaga, A. Huerta and F. Bertolotto coordinated the fieldwork and the creation of the databases in their countries, reviewed the results, contributed with ideas for interpretation and to the introduction and discussion of the results. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

The authors are most grateful to patients and institutions that participated in the study and generously shared their time and opinions with the aim to improve the quality of healthcare provided. We thank Kate Bartlett for the English version of this article, and to the European Commission Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007–2013) which is funding this grant agreement (no. 305197).